Once, several years ago, as part of a meeting-seminar with my friends from Nizhny Novgorod, we talked about Fair Play. That year there were several cases where violations of the competition led to the fact that athletes found themselves in unequal conditions. Today I would like to make another reference to the topic of fair competitions, but from the other side.

Of course, our sport involves many factors that lead to the fact that athletes almost never have perfectly equal conditions. For example, even where athletes run the same course, but with a separate start, those who start in the later minutes receive paths that were not there at the beginning, and this can either help or hinder the athletes. However, in those competitions where the race involves forking (relay, mass-start), a good fair forking is a very important factor that can greatly influence the placement of teams and athletes in the final protocol, as well as the excitement of the competition for spectators and athletes.

Spoiler: Everything is going very well with the relay race at World Cup. There is no criticism in this article; instead, using the example of the World Cup relay, we can trace what exactly happens when the forking is done fairly, and what happens if the forking is unequal. We just try to raise the current topic in the world of orienteering and discuss the equivalence of forking, the meaning and criteria of their equivalence, and invite them to discuss this topic.

The main task of forking is to create intrigue for spectators, complicate the work for athletes, and also prevent runners just follow each other without reading map. And it should not give an advantage to any of the options. At first glance, everything is fair, because subsequent stages will run through other options, which means that in total everyone will run the same distance. Technically, any forking is fair if three stages in different order have passed all three options. But let’s take a look at the first stage. If one of the options gives an advantage of more than 15-20 seconds, then this means that the owners of the long option will most likely lose visibility of the leading group of lucky ones with the short option, and this will lead to an advantage of some teams over others, but not on the principle of “who really stronger and more technical.” If there are several unequal forkings at course, then some teams will collect all the long options and most likely will fall further behind, but not because they are weaker. They will lose the advantage of running in the leading group, and perhaps will sag further in speed. All this does not add entertainment or intrigue, but rather the opposite.

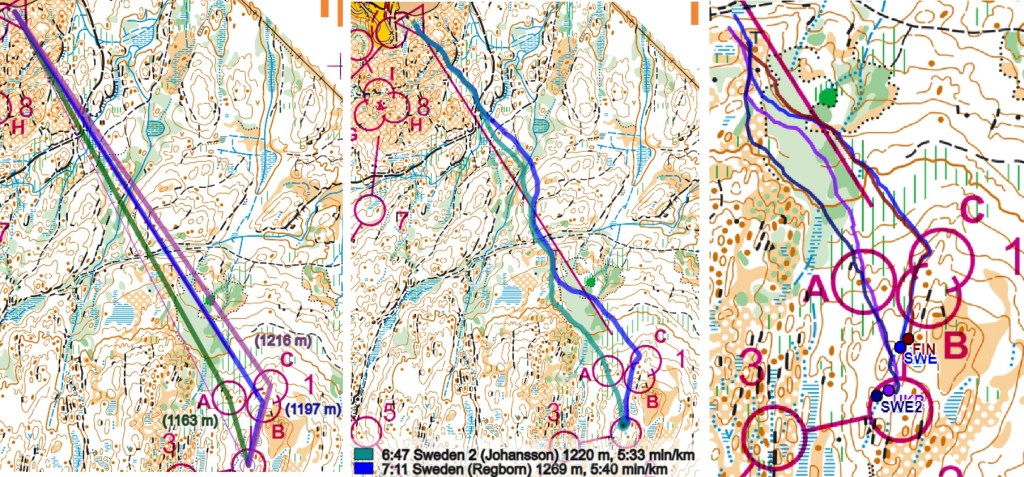

At the first control of the World Cup relay athletes are offered a standard set of three options:

Option A is shorter than option B by 35 meters, and shorter than C by 53 meters (picture on the left). For the first stage, this is a significant difference, because participants with option A receive a significant advantage of more than 20 seconds over athletes with C (picture in the middle: the best athlete on A and the best athlete on C). The participants who actually ran together (the tails of the track in the picture on the right) are scattered only due to elongation in the sifting, which gives an advantage to the leading group. The leaders of the long forking join the slower participants of the short forking and with considerable probability may have a decrease in speed.

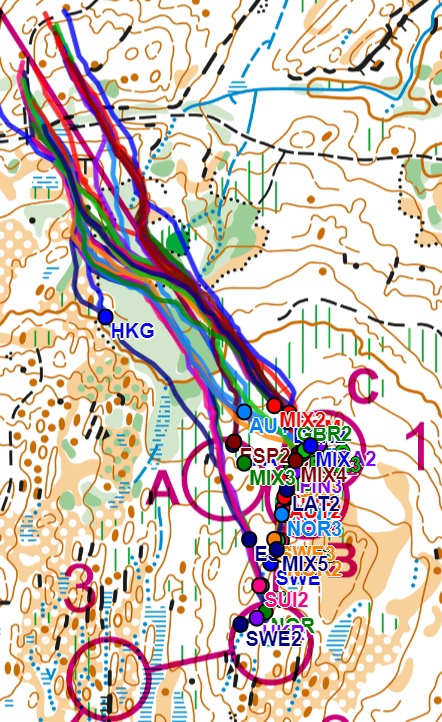

However, do not forget that at the first stage the picture actually looks like this:

This means that at the first leg, in the first half of the race, a continuously stretching “tail” of participants is formed in the forest. At the first stage, it is still possible for a runner with longer forking group to see his opponents running ahead and try to “catch up” with the leaders, using good physical shape. Thus, if an athlete from a long forking reunites with a group of short forking, he/she brings a significant advantage to their second and third legs, which will have a shorter forking but who will run in smaller groups (not possible to see the big “train” as it was at the first leg), and therefore will have a greater advantage than the owners of the short forking of the first leg. It is important for the planner, the athlete, and the coach to understand this.

Summarizing what has been said, it is important to understand that unequal forking brings different temporary advantages at different legs, and the sum of advantages for the entire relay for different teams is not the same at the end. Therefore, this type of forking is technically fair, but in reality, unbalanced forking affects the results. Any random team can get a better or worse situation.

If one of the controls has a simpler approach or there are common areas of movement that are more optimal for approaching to one of the forkings than to others, then this also makes adjustments to the length of the forking and technical complexity.

All of the above does not mean that forking should be prohibited. I would just like to highlight a situation that clearly indicates that the planner should take such factors into account when preparing relay. The better the forking is worked out, and the more equivalent it is in terms of technical parameters, the higher the interest and intrigue of the competition, the higher their quality.

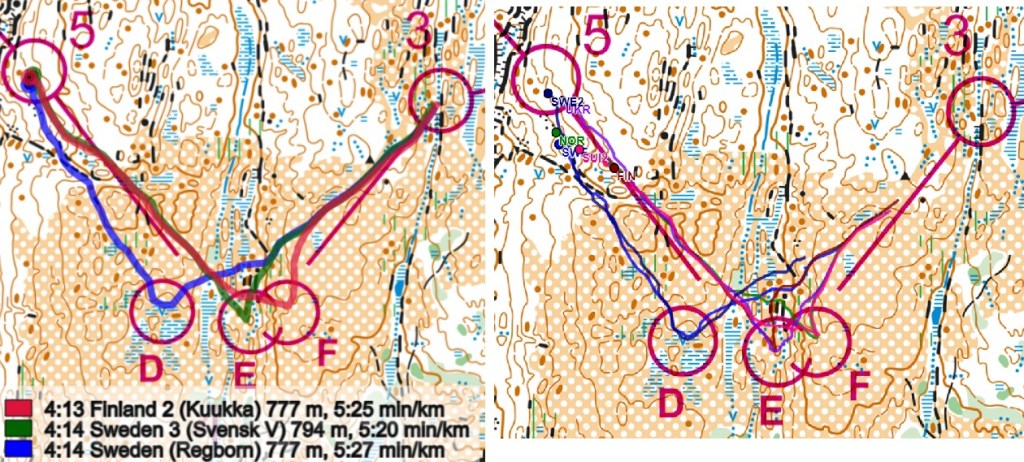

But for example, the second forking at the World Cup relay:

In this case, the forking is equivalent. The lengths are close to each other, and, as we see, the participants passed the forking second to second. If we pay attention to the distance between the participants before entering the forking and after it, we see that it has stayed he same.

The point of forking is precisely in that participants who have passed their controls in forking without times losses (without technical errors and maintaining speed) must meet after forking and no one should have an advantage.

We can develop the topic of forking by talking about individual competitions, where butterflies or Phi-loops are used, or when athletes go to completely different circles (Loops) sometimes in different parts of the map. The basic rule for such distances is that the presence of one or another forking should not give the participant an advantage. For example, if one part of a long course in “Loops” is on a more runnable part of the map with a lot of roads, and the other part is on a green, rocky part, then there is a significant difference in what order the laps are run.

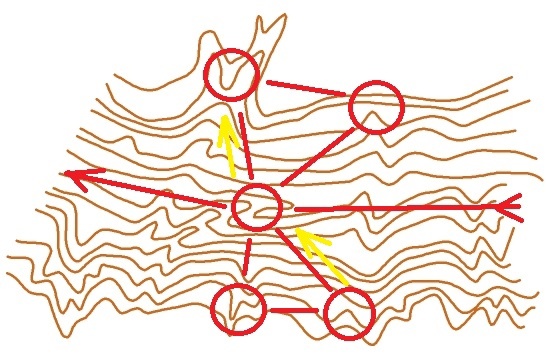

One more example. Butterflies on mountainous terrain, where one loop of butterfly is located above the other (see picture), and the entrance and exit from the butterfly is horizontal, will mean that the athlete who at first has the lower circle and then the upper one, will collect two climbs in a row (two yellow arrows in a row), while the competitors before and after him will run first the upper circle, and then the lower, which will mean splitting a large climb into two shorter ones, and one long descent instead of two. Therefore, to comply with the principle of equivalence of forking, it is better to place the butterfly symmetrically, where both loops will have a similar profile, i.e. along the slope, not across.

This topic has a lot of room for study, deepening research, and identifying patterns. But it is already clear now that the better the forking is worked out, the more interesting the fight.

Leave a comment